Vietnam’s civil society and ethnic minorities

Introduction

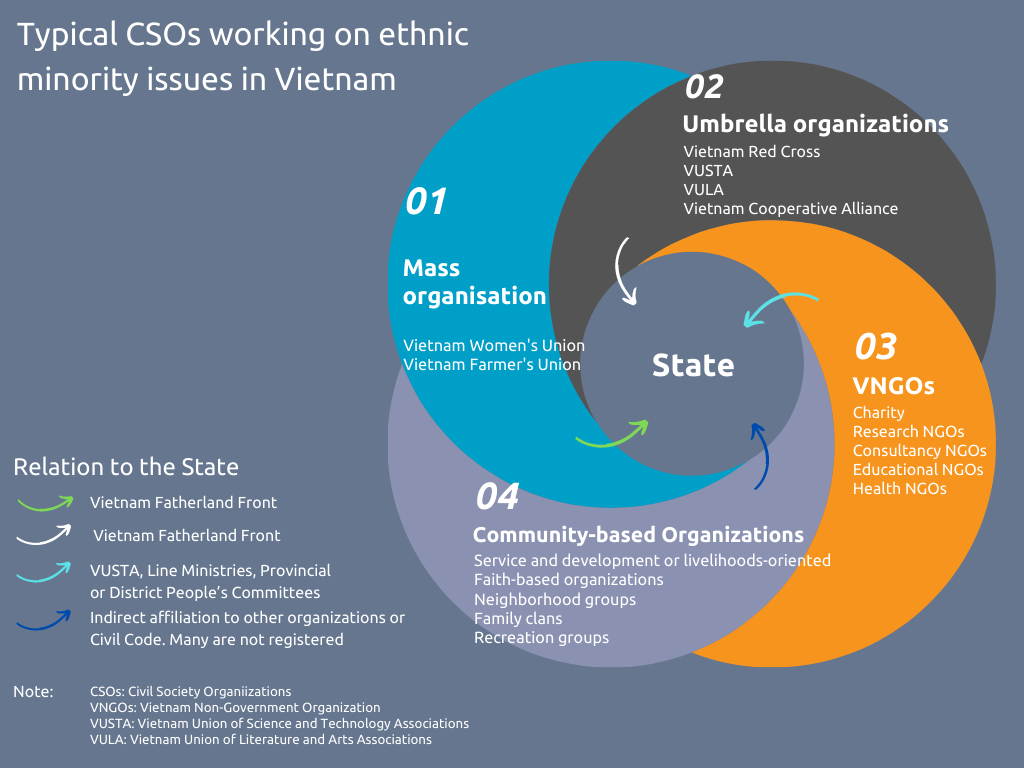

In Vietnam, ethnic minorities are supported by a network of non-governmental organizations, known as “civil society”. Civil society includes international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), Vietnamese mass organizations, Vietnamese umbrella organizations, Vietnamese NGOs (VNGOs), community-based organizations (CBOs), and professional organizations, although professional organizations work rarely related to ethnic minority issues.1 Together they work to promote inclusive growth, and protect indigenous knowledge and religious customs. However, their work occupies a sensitive space marked by difficulties.2

There is no clear framework yet that distinguishes civil society organizations (CSOs) from other organizations. The development of the “Law of Associations”3 has been delayed. Most organizations still describe themselves as VNGOs4and many are established under an umbrella organization. Their independence is questioned, as they receive government financial support, lack broad beneficiary representation, and may not be non-profit.5 Vietnamese mass organizations, also called “socio-political organizations” under the Vietnam Fatherland Front, are also commonly closely managed by the government. It has been suggested that an organization should be considered “civil society” if it engages in relevant actions, even if it is associated with the state.6

Source: Adapted from Irene Norlund, 20177. Created by ODV. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Civil society programs in support of ethnic minorities

The mass organization – Vietnam Fatherland Front8 has an Advisory Council on Ethnic Minorities. Under the Fatherland Front, the biggest member mass organizations working on ethnic minority issues are the Women’s Union and the Farmers’ Union.9 Their network reaches to the commune level, so INGOs and VNGOs often partner with them to conduct field work. However, mass organizations mainly mirror the approach of government agencies.10 Ethnic minority groups are rarely included as members. Those that are sometimes distance themselves from the needs of their communities.11

The main Umbrella Organizations with VNGOs working on ethnic minority issues include the Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations (VUSTA) and Vietnam Union of Arts and Literature (VUAL). They do not implement activities in the field, but regulate the operation of organizations under their umbrella and liaise with the state.

Most field activities relating to ethnic minorities are undertaken by INGOs, VNGOs and CBOs. However, many CBOs are unregistered, so tracking their activities is difficult. In 2002, INGOs and VNGOs jointly established an Ethnic Minorities Working Group (EMWG) which serves as a platform for sharing experiences and lessons learned regarding ethnic minority development in Vietnam. The EMWG uses a bottom-up, inclusive approach to its programs, research, and advocacy, but has had mixed success. They mainly focused on “soft investment” in production support, capacity building, cultural development, and promoting voice and participation at the grass-roots level. They also allocate resources on research and policy commenting and advocacy based on evidence from their pilots. The EMWG has encouraged government policy shift from “heavy subsidy” to “incentive facilitation”. However, programs suffer from limited resources, and impacts are hard to measure. In short, EMWG and its members are assessed to be quite strong in empowering citizens and supporting livelihoods, moderately good at responding and meeting to social needs but not very active or successful in influencing policy or the budgeting processes and raising authorities’ accountability.12

Ethnic women riding bike in Lai Chau province. Photo taken by Adam Cohn. Licence under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

International donors also support ethnic minorities. Some programs directly fund INGOs and VNGOs. For example, the Canadian government sponsored the project “Women of Ethnic Minorities Leadership Incubator” through the Institute for Studies on Society, Economy and Environment (iSEE). Other programs are mainstreamed within government administration system which raises concerns about the use of conventional “top-down” approaches. For example, the World Bank has provided $153 million in support of Vietnam’s National Target Programs to improve rural infrastructure, expand work opportunities and build government capacity in service delivery, particularly for ethnic minorities in 18 provinces.13 Yet other donors, like UNDP14 and IFAD15, do indirectly support ethnic minorities through poverty reduction programs targeted toward rural areas.

Women workers’ tea break. Photo taken by Adam Cohn. Licence under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Challenges and potential for civil society in Vietnam

The environment is the most challenging for VNGOs and CBOs. Resources are limited, and funding sources are expected to further decrease given Vietnam’s transition into a lower-middle-income country in 2010. The delay in the development of the Law of Associations prolongs uncertainty and limits the openness of public space for discussions. Staff need better facilities and support in skills building. Finally, not all VNGOs and CBOs are recognized by local authorities. With a narrow membership base and the need to ally with mass organisations to implement in-field activities, progress is slow and administrative workload is high.16

With more openness and integration, civil society could blossom in Vietnam. It is hoped that collaboration with the private sector would help achieve more independence from government.17

References

- 1. CIVICUS, VIDS, SNV, UNDP. 2006. “The Emerging Civil Society: An Initial Assessment of Civil Society in Vietnam”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 2. William Taylor, Nguyen Thu Hang, Pham Quang Tu, Huynh Thi Ngoc Tuyet. 2012. “Civil Society in Vietnam: A Comparative Study of Civil Society Organizations in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh city”. The Asia Foundation. Accessed May, 2020.

- 3. After decades of debate, the Law of Association was drafted in 2016 but then subject to lengthy delay for approval without specific deadline.

- 4. Ben Kerkvliet, Nguyen Quang A, Bach Tan Sinh. 2008. “Forms of engagement between State Agencies and Civil society in Vietnam”. VUFO – NGO resource center, Ha Noi. Accessed May, 2020.

- 5. CIVICUS, VIDS, SNhttps://data.vietnam.pp.opendevelopmentmekong.net/library_record/forms-of-engagement-between-state-agencies-civil-society-organizations-in-vietnam-study-report, UNDP. 2006. “The Emerging Civil Society: An Initial Assessment of Civil Society in Vietnam”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Irene Norlund. 2007. “Filling the Gap: The Emerging Civil Society in Vietnam”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 8. In Vietnam, the Vietnam Fatherland Front is a political alliance and voluntary union of the political organization, socio-political organizations, social organizations and prominent individuals representing their class, social stratum, ethnicity or religion and overseas Vietnamese.

- 9. VUFO-NGO Resource Center, “Key Agencies Working on Ethnic Minority Issues”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 10. World Bank. 2019. “Drivers of Socio-Economic Development Among Ethnic Minority Groups in Vietnam”. Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group .Accessed May, 2020.

- 11. CIVICUS, VIDS, SNV, UNDP. 2006. “The Emerging Civil Society: An Initial Assessment of Civil Society in Vietnam”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13. World Bank. 2007. “New World Bank Financing to Bolster Vietnam’s Efforts to Spur Rural Development”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 14. UNDP. 2012. “Support to the implementation of the Resolution 80/NQ-CP on directions of sustainable poverty reduction 2011-2020 and the National Targeted Program on Sustainable Poverty Reduction 2012-2016”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 15. Vietnam Business Forum. 2019. “IFAD Committed to Continuing Partnership with Vietnam to Reduce Poverty”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 16. CIVICUS, VIDS, SNV, UNDP. 2006. “The Emerging Civil Society: An Initial Assessment of Civil Society in Vietnam”. Accessed May, 2020.

- 17. Do Ngoc Thao. 2018. “The future role of civil society in Vietnam in 2030”. MA Governance and Development – University of Sussex. Accessed May, 2020.